The

Wealth of Care

A journey into the Surikí Nature Reserve.

1

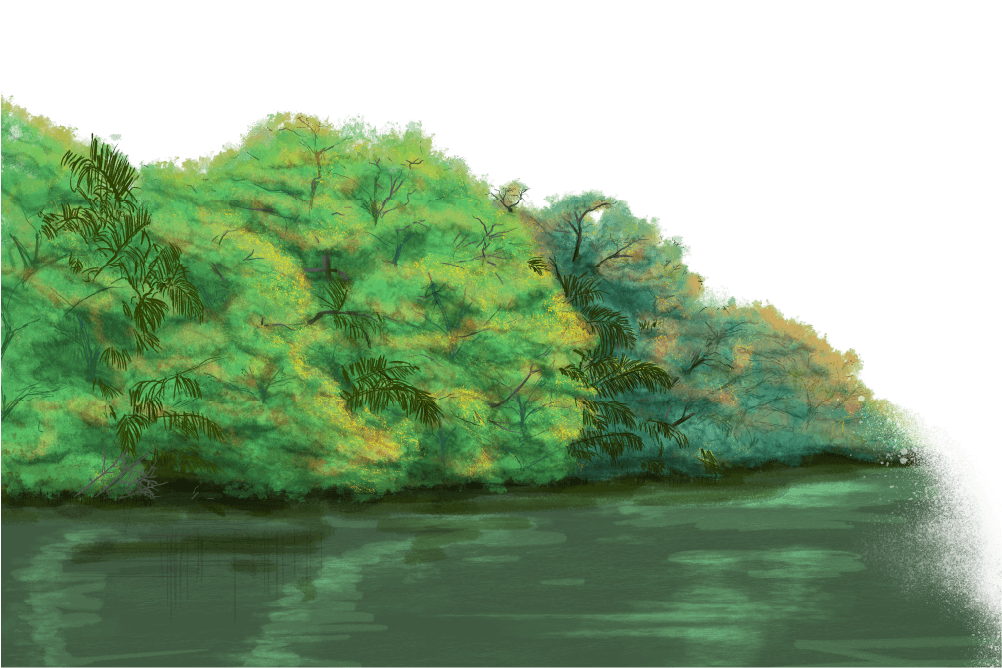

Before it spills into the Gulf of Urabá, the Suriquí River runs the color of burnished copper, slipping through a stand of cativo trees. There are no rapids, no vertiginous turns—just a slow, deliberate current that, on windless days, turns the water into a mirror. Fronds and vine tangled canopies study their own reflections; howler monkeys emerge in family bands to greet the skiffs that occasionally break the quiet with a boatload of visitors. Where the forest seems to draw itself into a dense green curtain on both banks, an opening appears: a small landing, a thatched reception hut, a hand painted sign. This is the entrance to the Surikí Nature Reserve, and the woman who steps forward to welcome visitors is Enilda Jiménez, a compact presence in her forties whose thoughts seem to arrive faster than her hands can punctuate them. She has dark eyes magnified by reading glasses and the practiced cadence of a host, but her origin story is not hospitality. It begins with an execution.

“They killed my father on October 6, 1995,” Enilda says. “By November, we were gone—displaced.” When the family tried to return a few months later, they found steel cables stretched across the Suriquí like sentries, blocking boats from coming in. Her brother Jaime—now sixty—had never lived anywhere else. Locals tied him up, threatened him, made it clear he had to leave the land. “It was hard,” she says. “First the guerrillas. Then the paramilitaries.”

“First the guerrillas. Then the paramilitaries.”

“His death left us without money”

2

Surikí sits on the western rim of the gulf, where three exuberant geographies converge: the northern fringe of the Chocó bioregion dissolving into the Darién; floodplains where the last coastal ridges of the Andes flatten and meet the sea; and, at the edge of it all, a Caribbean bay the shape of a great scallop. To get here, you board a skiff at Nueva Colonia, pass beneath the long new pier of Puerto Antioquia, then find the river mouth. Thirteen kilometers upstream—two hours in the slow water—you reach the reserve.

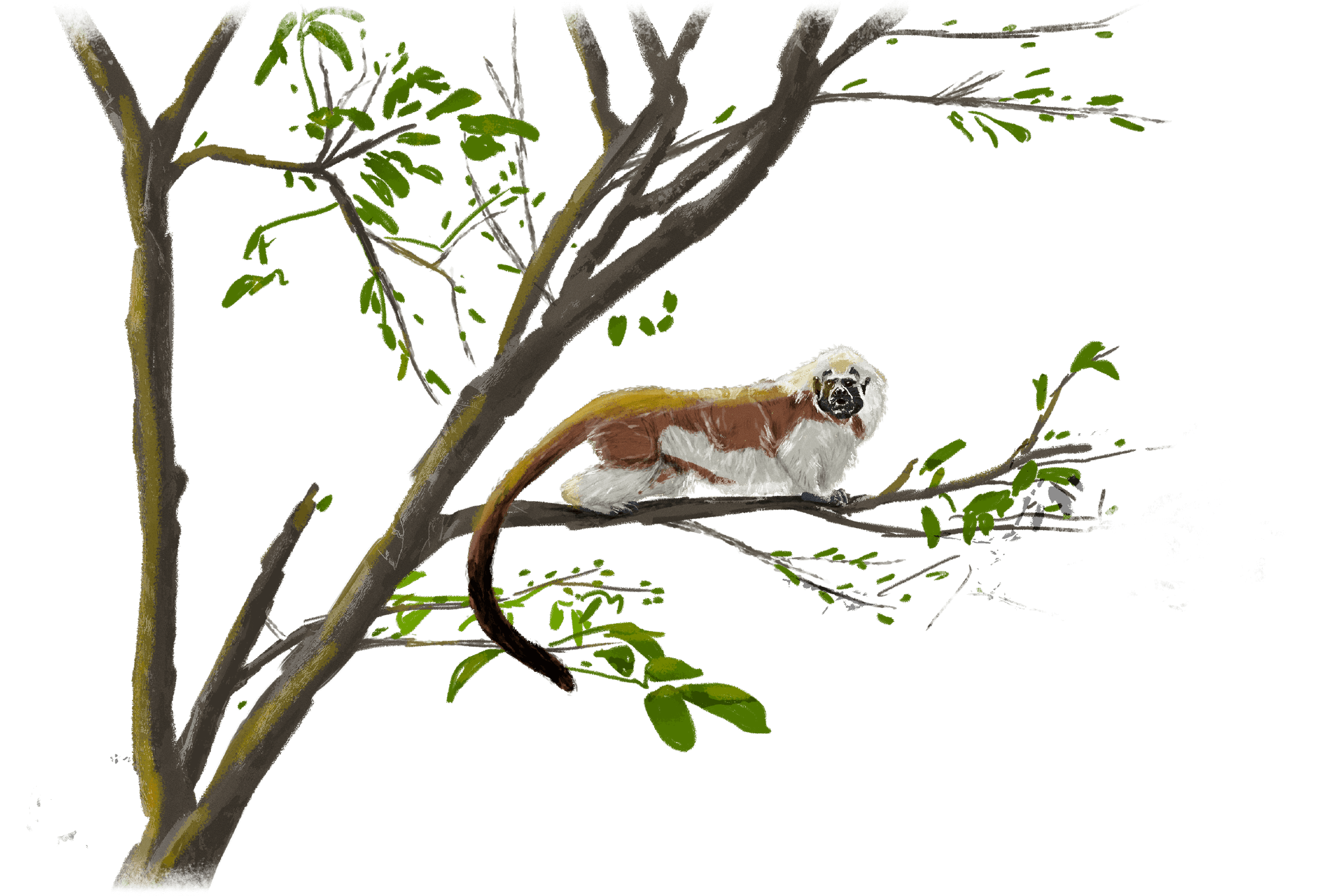

The numbers hint at why this pocket matters: at least 131 vertebrate species live here. Some, like the cotton top tamarin and a local bird known as the buco de Noanamá, are all but confined to Colombia’s northwest. Spider monkeys find safe habitat in the forest; jaguars, manatees, and the horned screamer trace the Suriquí as a protective corridor.

“They killed my father because he refused,” Enilda says. “He was offered a place in the machinery that so many were forced to join. He said no—and I’m sure he knew it could cost him his life.” In the Justice and Peace cases against the Banana Bloc of the A.U.C., the murder of Samuel Antonio Jiménez—a respected rancher and smallholder—appears as a paradigmatic crime. The men who set it up were neighbors, people the family had known since childhood. “They said he was a guerrilla collaborator,” she recalls, though he was not. “It was a way to take his land.”

The family would come, years later, to reframe the loss. When they finally began to rebuild—fourteen hammocks strung beneath a plastic tarp for a roof—someone asked, What if Dad had said yes? The silence broke into tears. The first answer changed how they would live: If he had joined them, we wouldn’t be alive. He kept us out of the war. “His death left us without money,” Enilda says. “But it gave us time—and a moral compass. When we argue, we still ask: What would our elders have done?”

3

Surikí was a working farm long before it became a civil society reserve. Samuel Antonio assembled it from three tracts: two he colonized and bought; one he received from the old land reform agency, Incora. Six hundred hectares, in a place the state, in the late nineteen sixties, wanted to “put to use.” He was a man of the countryside, born in San Pelayo, Córdoba. He felled forest and planted bananas, ran cattle, hunted what the land gave. In the eighties, Colombia’s two largest insurgencies—the FARC and the E.P.L.—pressed into the lower Suriquí. The FARC arrived first, taxing landowners in money, food, medicine. Like many, Samuel paid to be left alone.

In 1990, as the E.P.L. negotiated peace with the government, a dissident faction under Francisco Caraballo turned to kidnappings—not just of the wealthy banana magnates from Medellín but also of local farmers the community admired. Samuel was taken for nearly two months; to free him, the family sold assets, his wife Armida Pineda delivering the ransom herself deep inside the dissidents’ camps. By the mid nineties came the paramilitaries of the Castaño clan. The whispers preceded the massacres: now the paras are coming. Some were terrified. Others, exhausted by guerrilla abuses, mistook it for hope.

The hope was a mirage. “In 1995 the killings began,” Enilda says. “I remember the mayor, Gloria Cuartas, carrying a folder of homicides she somehow managed to upload to the early Internet, to show the world what was happening in Apartadó and across Urabá.” On October 6th, Samuel left San Jorge after inspecting farms he managed. Reduced by the earlier ransom, the family was struggling. He drove his white Toyota on the road to Nueva Colonia. Two men on a motorcycle began to tail him. In the car with Samuel were two of his nieces and two young men he’d offered a ride. Sensing danger, he turned off toward Nueva Colonia. At a crossroads, he pulled over and said he wasn’t going on. One of the men inside the car shot him first. The gunmen on the motorcycle finished him with shots to the head, in front of his nieces. The killers took the Toyota, using it for months to shuttle between murders, to move the dead.

At the time, most assumed the guerrillas had done it. Samuel—banana grower, rancher—fit the insurgency’s target profile. Only later would the architecture of the crime come into view. Years on, authorities found the stripped chassis of a white Toyota on a farm tied to Hebert Veloza, known as H.H., a paramilitary commander. The plate led back to Samuel. In a Justice and Peace hearing, H.H. was asked who the owner was. He didn’t remember; his lieutenants did. “That was the man we killed,” they said. “Carlos Castaño gave the order.”

The family’s road back began there. They met Raúl Emilio Hasbún, alias Pedro Bonito, the Banana Bloc’s political chief, who’d offered a farm in partial reparation. The case was contested. “He told us, ‘I had men on your property; I’ve already removed them,’” Enilda recalls. In 2014, with state accompaniment, the Jiménez siblings returned. By 2017 and 2018, they had raised a small house.

4

Today, most of the twenty siblings live between the reserve and nearby rural districts. A few are in town. By Enilda’s count, there are at least 112 nieces and nephews—plus the great nieces and great nephews arriving annually. The big decisions are taken in assembly. Everyone accepts that Enilda is the leader—the head of a family enterprise built on the ashes of loss.

Just under seventy per cent of the six hundred hectares is set aside for conservation. From that base, the family has built a regenerative tourism project—part field school, part refuge—visited by biologists, social scientists, university groups, and travelers who come less for comfort than for the lesson the forest teaches. The remainder of the land is run as agrosilvopastoral pasture: trees and shrubs stitched into the paddocks, rotated cattle, forage carefully managed. For the combination of ecological restoration and social repair, the reserve has received Colombia’s Peace Destination Seal (from the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism) and the Green Business Seal (from Corpourabá).

There is another kind of accolade here—one that involves no podium or certificate. A hundred or so yards from the house, camera traps watch a path the cats have worn. In the Andean foothills or the colonized edges of the Amazon, jaguars flip past a lens like rare apparitions. At Surikí, they appear several times a week, most weeks of the year. One evening, a brother—stepping out into the dark—found himself yards from a mother jaguar and two cubs learning to hunt near the cattle. He did not fetch the shotgun. He stood still and watched until they melted back into the trees. Today, the family protects its herd with lights, bells, and loud blanks.

“When we returned, we brought cows,” Enilda says. “It’s what we know. And the jaguars started taking some.” The family argued. Some wanted to clear more forest and hunt the predators. “We—the younger ones, and the women—asked, Really? Is that how we begin again? We come back from our father’s murder only to repeat violence against the lives of jaguars, monkeys, peccaries? Are we going to restart this story by doing to these species what was done to us?” The question changed the trajectory. The family commissioned a biological survey: sixteen species at risk used the property. “We realized we had a lot in common with the jaguars, the manatees, the primates, the birds, the frogs,” she says.

They mapped the land, set hard rules. Keep the conservation block intact. Run cattle differently. Adopt silvopasture. And then—more ambitious still—build a business model around ecosystem services. The reserve is developing a habitat bank—a mechanism to channel biodiversity credits from large infrastructure projects to places like Surikí, where the money can be translated into protection, and protection into a livelihood. “What we want,” Enilda says, “is for conservation to become both a way of life and a way to make a living—to understand that wealth can be connected to the care of life.”

“We realized we had a lot in common with…

5

“Surikí insists on a different proposition —that prosperity, like the river itself, can move at the speed of care.”

Stories of Peace

and Territory