1

Into the

Interior

“You enter

quietly and

with respect,

because here

the path is part

of the home.”

2

The Land That

Holds Us

The Guna Dule indigenous community, also known as Kuna, understands the land as a being with memory. In their songs you hear Nana Dummad, the Great Mother, and Ibeorgun, the sage who threads the visible to the invisible.

Cultivating, then, is not just producing. It is a conversation with what sustains life. Molas are layered cotton panels worked in reverse appliqué, colors revealed as the fabric is cut and turned, finished by hand with fine stitching. Born from ancestral body designs carried to cloth in the late nineteenth century, they form the heart of the traditional blouse, the dulemor. Their patterns trace labyrinths, rivers, and fields alongside birds and leaves, intimate maps that connect people to nature and safeguard memory and identity, stitch by stitch.

3

Caimán Nuevo,

Necoclí, Urabá

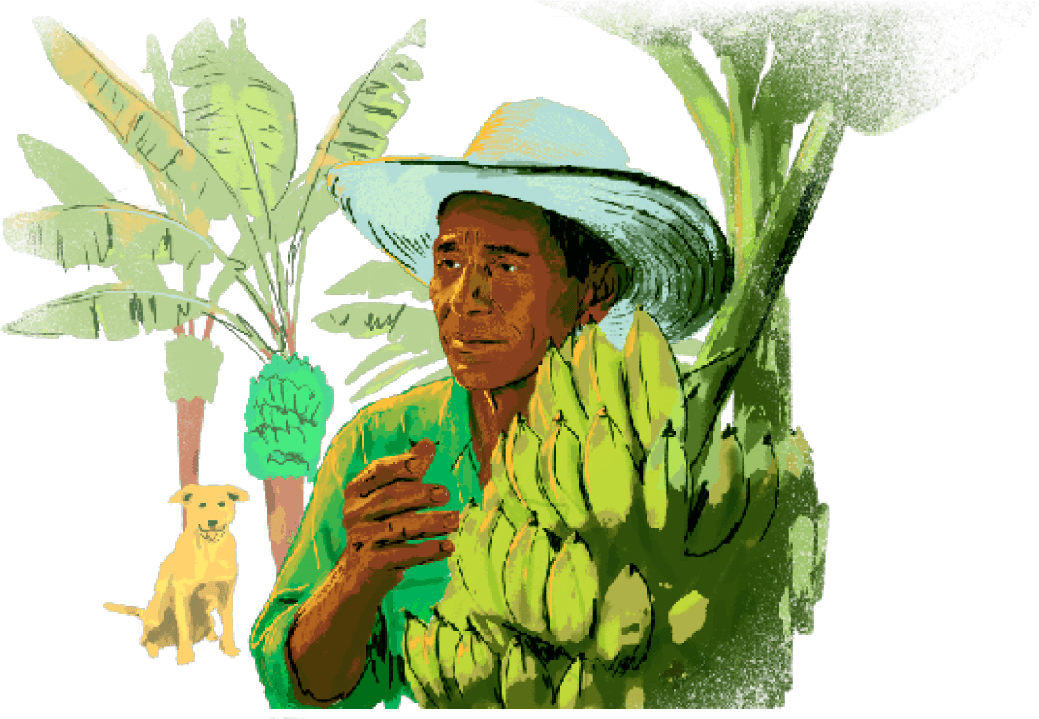

4

María Corina Achán, Small Grower

“If you feed

the land,

the land

answers.”

5

Albeiro Achán

“We’re given this

land to care for.”

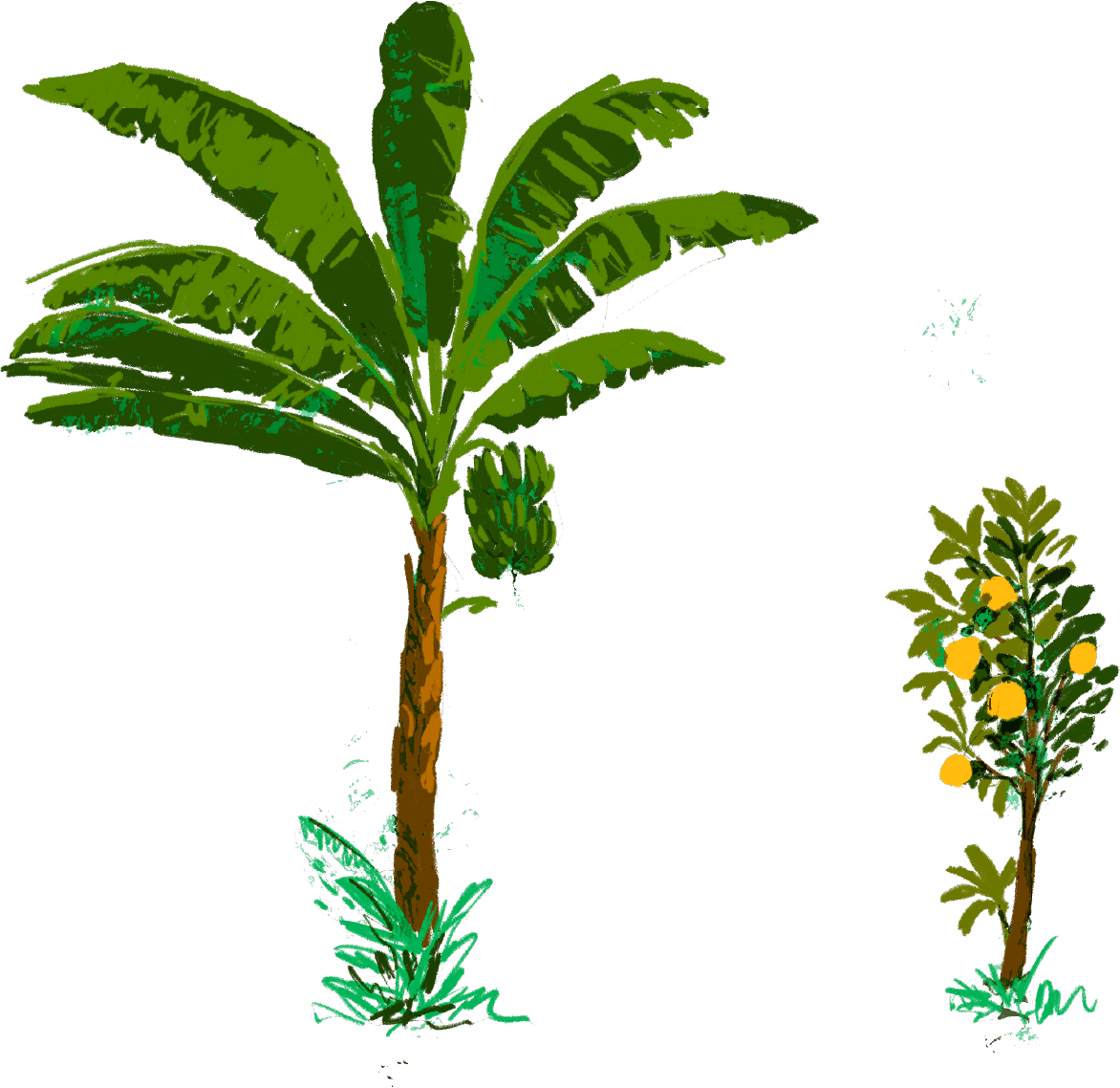

6

Where Quality Begins

The conucos, traditional crop plots, breathe in mixtures: plantain beside coconut and lemon trees. A conuco here is a polyculture plot where staple plants and shade species live together. Diversity protects the soil and spreads risk. If one crop fails, another carries the table. The wind brings aromas of fresh coconut, lemon blossom, wet leaf. That closeness steadies the microclimate and lifts the fruit: firm flesh, clean peel, a contained sweetness that travels well.

The soil, dark and slightly clayey, is tended with mulch, layers of dry leaves, plantain stalks and peels, straw, and crop residues that hold moisture, slow weeds, soften heat, and, as they break down, feed the earth. Infiltration trenches let rainwater enter slowly, prevent erosion, and recharge the subsoil. Most fertilizers are homemade and organic. The rule is not to force things. The plant sets the pace.

7

The Work We Hold in Common

“Everything flows at the rhythm of the culture and the land.”

8

Shared Value in Place

9

Plantain, the Territory’s Backbone

10

The Ethics of the Conuco

“It bends. It does not break. It opens new leaves.”