What We Endured in Osaka

1

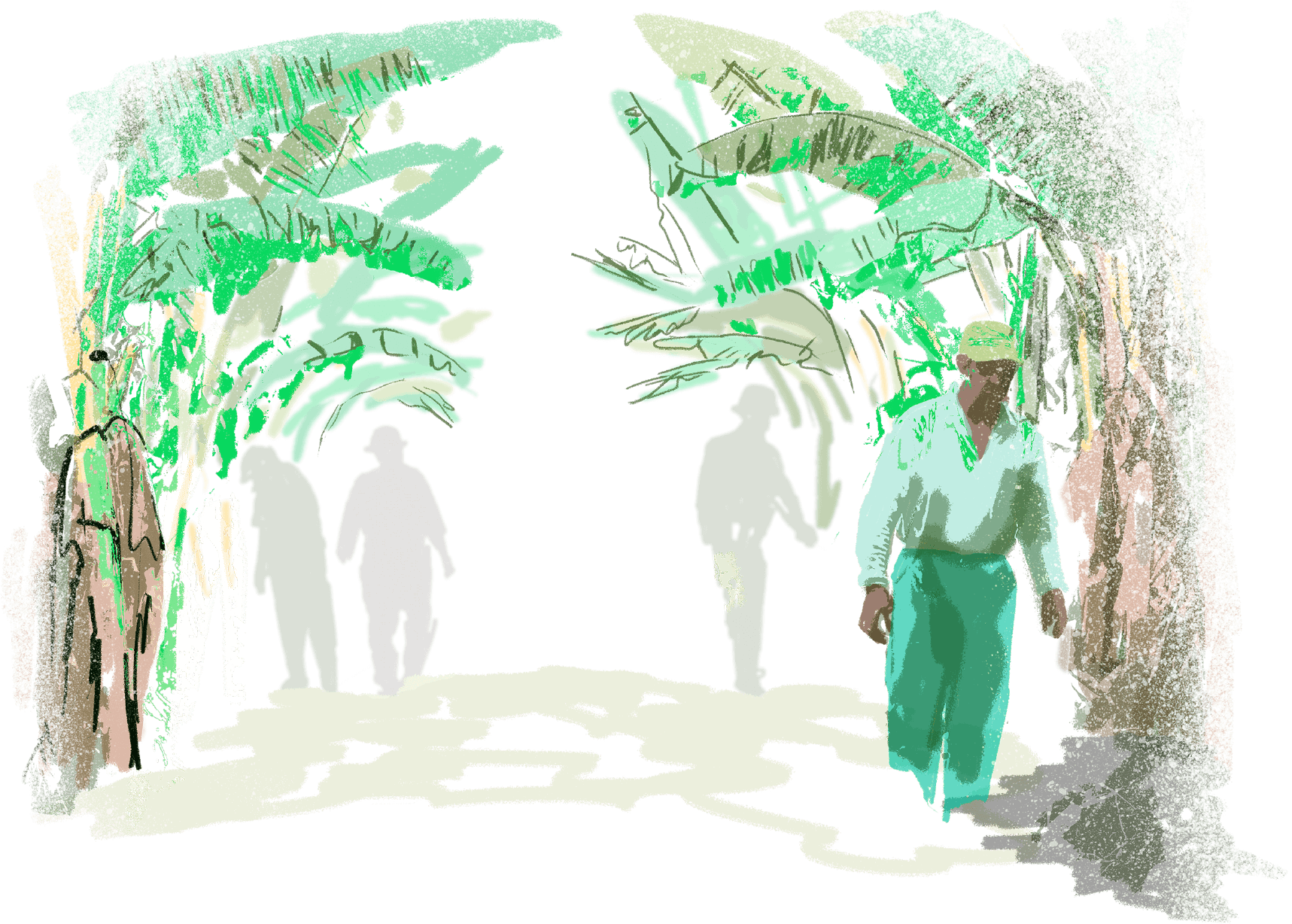

At the heart of a banana plantation stands a cenotaph as tall as a person. It could be a mausoleum, except that it presides over no grave. There are no tombs around it, no mass burials, nothing that holds human remains, only the even, quiet landscape of plants with their bunches sleeved in sky-blue plastic.

On February 14, 1996, eleven

workers from the Osaka farm,

located in Communal 10,

municipality of Carepa, were

massacred by the Fifth Front

of the FARC.

In homage to the victims and survivors, so that these acts will NEVER AGAIN be repeated.

Below the inscription, the names of the eleven victims run in a vertical list. The first is a woman, Myriam Padilla, who was twenty-six when she fell in that massacre. Her widower stands beside the cenotaph, his expression tender and melancholy. He says that remembering that day makes him very sensitive. His name is José Humberto Moreno, he is fifty-eight. After losing Myriam he married twice, became a father, and managed to build a full life. There are moments, though, when he turns inward and wonders about the turns his life has taken, how Myriam might look today, what their family would have been like. What happened does not leave you, it does not leave your head, he says. Time can pass, and if someone asks me, I can recount every detail of that day.

The Osaka massacre, as it entered the record of Colombia’s armed conflict, was the last carried out against banana workers organized in Sintrainagro. According to military authorities at the time, it was a FARC reprisal against supposed army informants who had helped capture nearly forty guerrillas of the Fifth Front in previous weeks. For José Humberto, who survived, it was a display of power. I believe it was about maintaining control of the territory. Later investigations by the National Center for Historical Memory and by the Truth Commission argue that this attack on civilians was one among many that the FARC had carried out since 1991 against anyone they associated with the demobilization of the Popular Liberation Army, the EPL.

“If the business died, we would all die with it”

2

In the late nineteen eighties, both groups were part of the Simón Bolívar National Guerrilla Coordinating Board, an umbrella that sought to unify strategies among the country’s main insurgencies ahead of possible peace talks with the national government. Alongside the FARC and the EPL were the M 19, the ELN, the Revolutionary Workers’ Party, and the Quintín Lame Armed Movement. In the final months of 1989 and the early months of 1990, EPL commanders in Urabá eased military pressure on banana entrepreneurs. They had taken stock of the damage the guerrillas had inflicted on these communities. Capital was fleeing, looking to Central America, drawn by stability in places like Costa Rica and escaping extortion, kidnapping, murder, and land seizures. If the business died, we would all die with it, Mario Agudelo, one of the EPL’s leading spokesmen, would later say. He demobilized and became a political leader.

Convinced by that logic, the Marxist Leninist EPL left the Coordinating Board and opened peace talks with the government. The process led to disarmament and an accord in February 1991, and gave rise to a political movement called Hope, Peace, and Liberty. Because of the territorial overlap in Urabá and their political proximity, the EPL kept the FARC informed and asked for tolerance. We reached out to them, Agudelo would later reveal, and they answered that they would respect the process. Those who did not were some sixty men under one of the EPL’s founders, a hard line communist commander named Francisco Caraballo. They broke off, accused their former comrades of surrender, and pledged to continue armed struggle. They cast those in the peace process as sellouts who no longer belonged in the organization. In other words, Caraballo believed that he and his men, even as a minority, were still the true EPL, and that the commanders and militants at the negotiating table were traitors.

The internal violence began quickly. By the end of 1991 about twenty members of Hope, Peace, and Liberty, known locally as esperanzados, had been selectively murdered. In time, the FARC found reasons to embrace or absorb Caraballo’s dissidents. Some of the esperanzados, they said, had allied with class enemies, cattlemen and banana entrepreneurs. Others had joined intelligence agencies and the security forces. Still others had been co opted by paramilitaries. The absorption produced a death squad called the Bernardo Franco Military Front, whose sole purpose was to attack people linked to Hope, Peace, and Liberty, no matter their level of political commitment, from sympathizers and activists to militants and union leaders.

By 1993, the FARC escalated the violence with massacres of banana workers on the plantations themselves. The first of the year was at Filipinas, on the outskirts of Apartadó. On February 26, gunmen mowed down five people. Then came Las Moras, on May 3, with eight victims, and San Rafael, La Ceja, La Lolita, and Santa Bárbara, with twenty one victims between November and December. When the EPL was part of the Coordinating Board, we always had good relations with the FARC, Agudelo would recall. We never expected this from them.

In homage to the victims and survivors, so that these acts will NEVER AGAIN be repeated.

José Humberto Moreno

3

José Humberto Moreno started working as a laborer at the Osaka farm in 1993. He was twenty six and had learned plantation work by watching his mother and his siblings. Every morning, he and his wife, Myriam, rose before dawn to catch the company bus that took workers from their homes in Apartadó out to the fields. There was a lot of violence in the region, he says. You left the house not knowing if you would come back. On the way to work you said to yourself, May the Lord’s will be done.

Massacres on the plantations were followed by massacres in the settlements on the edges of town, the housing projects built for Sintrainagro workers. The bloodiest was in La Chinita, then an outlying sector of Apartadó, now the Obrero neighborhood. On the night of January 23, 1994, after a rally for Hope, Peace, and Liberty, FARC gunmen opened fire on anything that moved. Thirty five people fell. The official explanations no longer stopped at ideological fanaticism and reprisal. Authorities began to argue that these collective murders were, at bottom, an electoral strategy to deprive the esperanzados of votes.

The following year, 1995, the massacres tripled. A new armed actor returned to the region, stronger and more brutal, the Castaño organization, now calling itself the Peasant Self Defense Forces of Córdoba and Urabá, the ACCU. The band was known for dismemberment. People called them the Head Choppers. They had started in Córdoba, but they mastered the intimate corridors of Urabá after absorbing a handful of demobilized EPL fighters who, in 1992, having survived FARC attacks, had organized a self defense band, ex guerrillas rearmed both to avoid being killed and to kill, to control territory and turn it into a rear base. Their name appealed to their insurgent class origin, Popular Commands. Their debut had come in December 1993 with the massacre of twelve banana workers at the Los Cativos farm.

The landscape of violence was now stark. On one side, the FARC, supported by EPL dissidents, were annihilating banana workers organized in Sintrainagro who had once belonged to the demobilized EPL, accusing them of informing for the security forces or for the Popular Commands, which meant collaboration with the ACCU. On the other, the ACCU, backed by rearmed EPL ex combatants grouped in the Popular Commands and with the acquiescence and guidance of senior security officers, were annihilating Sintrainagro workers whose political profile linked them to the Colombian Communist Party or the Patriotic Union, accusing them of being covert FARC fighters.

Between August and September 1995, at least sixty six people were massacred in the four municipalities of the banana belt. First came El Aracatazo, in Chigorodó, where the paramilitaries murdered nineteen people. Then the FARC killed sixteen at the Los Kunas farm, in rural Carepa. Paramilitaries followed with seven dead in Turbo. The FARC answered with twenty four dead at the Bajo del Oso farm in Apartadó.

4

On February 14, 1996, at five in the morning, Myriam and José Humberto boarded the bus to Osaka. The sense of looming slaughter had followed them like a shadow, although it had not yet fallen on them. God willing, it will not be our turn, they told each other. The dirt road into the farm was full of holes and ruts that forced the driver to slow down. Then several armed men jumped into the road and brought the bus to a halt. Not all of them wore masks. One seemed to be dressed in olive green, a uniform much like the police.

Two of the gunmen climbed aboard. This is our turn, José Humberto thought. They ordered the passengers and the driver off and lined them up at the front of the bus. A man with a rifle slung over his shoulder began asking each passenger what job he did on the plantation, then sent him toward the rear of the bus. I tie bunches. Go to the back. I am a packer. Go to the back. There, another gunman forced them to lie face down on the bare earth.

Once eight or so workers had been made to lie down, they called up a man who was a close friend of José Humberto. At some point he had confessed that, if the killers ever surprised him, they would have to kill him running, not tied up or on his knees. I do not know if it was divine will or chance, José Humberto says. They took him to the back, and when the man turned to keep pulling people off the bus, my friend bolted. When they realized it, they started shooting. Everything turned to chaos. Most people ran. Others of us did not have the courage to run. We did not even have the courage to lift ourselves off the ground.

When the gunfire stopped, more than ten workers lay on the ground at the front of the bus. Among them were Myriam and José Humberto. They had thrown themselves down by reflex, trying to avoid the bullets. One of the gunmen, a FARC militia member known in the region as alias Papujo, took advantage of having them on the ground and began killing them one by one, a point blank rifle shot to the head. My wife and I were near the end of the line, from where the man started shooting, José Humberto says. When I saw him getting close, I touched my wife so we could try to run, and I felt her rigid. I shook her and saw she seemed dead, no sign of life, as if the fear had given her a heart attack. When I realized she was dead, I wanted to get up and run, but I could not. My legs would not respond. On all fours, like a dog, I crawled a few yards and threw myself into the irrigation canal.

Osaka was a relatively new plantation. Its channels, used for constant watering, ran full of muddy water. The gunmen, confident that their rifles could do it all, did not worry about the canal running parallel to the road. Buried in the muck, José Humberto realized that several other workers were hidden there. That canal saved many of us. After a while, when we did not hear shots, the driver climbed out and said, Boys, they are gone. We all came out covered in mud. No one waited for the police, for the coroner, or to give a statement. Let us get home now, the driver said, and that is what we did.

In the confusion and shock, José Humberto hurried to his house. Myriam had a thirteen year old son, and he needed to tell the boy before he heard it from someone else. I gathered my courage and told him the truth. He was inconsolable. It was a hard moment. He did not know his father. I was his stepfather. It hit me very hard.

Even now, his eyes well at the memory. His voice trembles as he moves through the story. Saying it here is one thing, but living it, living that moment, that is, it is rough, it is hard. People urged him to leave Urabá, to start over somewhere else. He considered it. He spent two weeks in the town of Los Córdobas, visiting his mother in law, delivering Myriam’s body, caring for the boy. He thought it through. He knew no trade other than banana work. His mother in law told him he could stay, but he did not see a future there. His own family, his mother and his siblings, were in the banana zone. They lived in the towns. They were his support. He did not feel capable of starting from zero, alone. Back in Apartadó, knowing that violence could take him at any moment, he told himself, God’s will be done. My family is here. If I am going to survive, I will survive here.

“God’s will

be done.

My family

is here.

“If I am going to survive, I will survive here.”

5

The season of extreme violence in Urabá continued for years. Records from different offices and institutions tell the scale of the barbarity. There were 763 attacks on former EPL combatants, including murders, attempted murders, and forced displacement. There were more than two thousand attacks on union members who sympathized with, or maintained ties to, Hope, Peace, and Liberty. Every armed actor committed abuses, although the FARC was the main aggressor.

Public records on the Osaka massacre say the eleven victims were sympathizers or militants of Hope, Peace, and Liberty. The truth is that several of the workers on that bus had no political affiliation and had never been part of the EPL. They were gunned down for belonging to Sintrainagro, which by then was seen as a union of the esperanzados. Paramilitaries and the security forces had assassinated and arrested most members with roots in the Colombian Communist Party or the Patriotic Union, and therefore linked to the FARC.

José Humberto puts it this way. Sintrainagro’s leaders were part of Hope, Peace, and Liberty. That is why they said that anyone in the union belonged to that movement. That is where the confusion came from, that by being members of the union we came from that guerrilla. We were stigmatized. That was the argument they used to justify the massacre.

It took six or seven years for José Humberto to begin to overcome the trauma. In that time he spent the savings he and Myriam had set aside to build a house of their own. It was a decent little sum, two and a half million pesos then, which would be around twenty five million today. I drank it all. He was paranoid. At night he felt knocks at the door. He felt someone behind him on the street. His head felt heavy, larger than it was. He heard the shots replaying between his ears. To sleep I had to drink half a bottle of aguardiente. Of the things he and Myriam had bought, a stereo remained. He had never learned to use it. Sometimes, desperate to hear music, he would turn knobs and press buttons that seemed to do nothing. At midnight, when he was passed out, the stereo would come on. I thought they were haunting me, that it was my wife’s spirit. Later I figured it was my fault, that I had pressed something that set a timer to turn it on at that hour, right.

Only when the National Center for Historical Memory arrived, in 2012, did José Humberto and the other surviving workers sit down to talk about the exact moment of the massacre, about the pain and the absence of those they loved. The Center formed a working group with survivors from the Osaka and Los Kunas farms and with families displaced from the Zungo river dock. There were workshops, shared topics, group therapy. It helped me a little. Before that, a co worker named Julio Pastor had led activities so that Osaka workers could remember the massacre. He was the one who helped them overcome a structural fear of harm, a fear that kept them from speaking certain words aloud, that kept them from talking to strangers about the FARC or the ACCU, that kept them from recalling the details of how they had survived.

My job was to help defeat the fear, Pastor says. Silence could not go on. People had to know. And with the Victims’ Law they had rights they had to claim. We managed to break the fear that had been there. The terror that if you spoke, consequences would come.

With the Center, survivors raised the idea of building the cenotaph. They sought permission from the plantation’s owners to install a site of remembrance. They spoke with public institutions for support, and with the Carepa mayor’s office and with Sintrainagro to accompany the ceremonies. We feared Osaka could disappear, that ownership would change, that it would be merged with other farms, and we would lose the exact place where the massacre occurred, Pastor says. We thought there had to be something that would make the site visible, so that when none of us were around anyone could find it and know what happened there. José Humberto carried a need for vindication that only the cenotaph could ease. The only woman who died in the massacre was my wife. That is why I wanted to keep this story from being forgotten.

José Humberto is a few years from retirement. The other survivors are as well. The risk they foresee is that no one will remain to care for the cenotaph or defend its place inside the plantation. No one will be left to keep showing what happened, José Humberto says. It is important that the site, at the very least, does not disappear. While they negotiate with the company for that guarantee, they ask to place a plaque at the farm’s entrance, so that anyone passing by will know what happened there. We do not know if, in the future, when we are gone, the owners will remove the cenotaph to plant more bananas. So we hope they will let us put something at the entrance, so that this is never forgotten.